How much education does a great author have?

Some time in the middle of high school I, like most students, had to start transforming a literal world of possible futures into a concrete decision about what I was going to do for the rest of my life. Ultimately I settled studying engineering in college, choosing this over literature/creative writing in no small part because I figured that a formal education was more important to being employed as an engineer than it was to being an author. After all, most great authors had no formal post-secondary education. Right?

Ultimately I decided to be neither an engineer nor an author, but rather a scientist (currently in training!). One of the most important things, heck, the most important thing I’ve learned about being a scientist is the need to distinguish between speculation and fact. Always check your assumptions! So at some point I got to wondering, is it really true that most great authors don’t go to college?

I looked up a few and saw that of course Shakespeare didn’t, and Hemingway didn’t, and Faulkner was a drop-out, but then I noticed that some of those regarded as contemporary greats, like Jonathan Franzen and Nicole Krauss, had MFAs and even PhDs. Well, this was interesting! Perhaps I was wrong, or perhaps historically higher education was unimportant but in recent years it’s become necessary to develop one’s writing (or at the very least, to get properly published).

So I decided to investigate the issue in an at least semi-systematic manner. First, I needed a criterion for “great author.” I decided to use winners of prestigious literary awards, namely the Nobel Prize in Literature, the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the National Book Award, and the Man Booker Prize. I chose those because they are relevant to western culture, in which most countries utilize a similar educational system with a similar degree hierarchy, and because they have a relatively lengthy history.

This of course comes with its own problems: awards don’t necessarily indicate “greatness” and “greats” don’t always win awards, sometimes awards are given for reasons other than merit (e.g. the allegations of political motives behind the Nobel Prize), and defining “greatness” as “award-winning” will tend to exclude those at the beginnings of their careers right now who in retrospect will be considered great in the future (especially significant for the Nobel Prize, which goes to a person and not an individual work, though I’d guess that bias towards established careers can be found for every award).

Still, it’s the best I can do for an objective definition of “great,” given the subjective nature of the concept. I dug up lists of all the winners of these awards and then searched online to find their highest level of education attained. Unfortunately for my purposes, most biographies don’t really list “so-and-so went to college and attained this degree in this year”, so it had to be inferred. This data came mostly from wikipedia.org and the nobelprize.org biographies, occasionally from other sources. I did not record the specific source for each case since these are basic facts and should be independently verifiable. If there is an error, please let me know (with some sort of documentation) and I will correct it.

I noted the highest level of post-secondary education completed at the time the award was given (there was a case of someone earning a higher degree after receiving their award), and recorded it in an Excel spreadsheet. I did not note (in most cases) the field in which the degree was earned since the vast majority were in English/literature. There was a relatively common minority degree, law, which also doesn’t evenly fit into the “Bachelor’s-Master’s-Doctorate” spectrum, so I did note that one separately in the raw data.

The possibilities were uncompleted undergraduate studies (“partial” in the spreadhseet), Bachelor’s (“BA”), Master’s (“MFA”), Doctorate (“PhD”), and law (“JD”). There were a few instances in which someone earned multiple degrees at one level; I simply counted these as one (so three Bachelor’s degrees is still just “BA”).

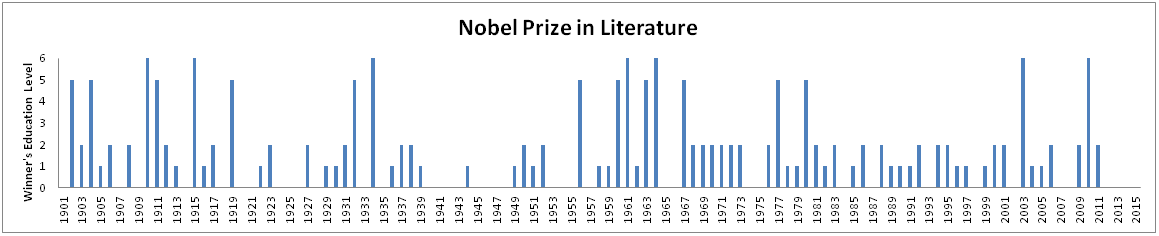

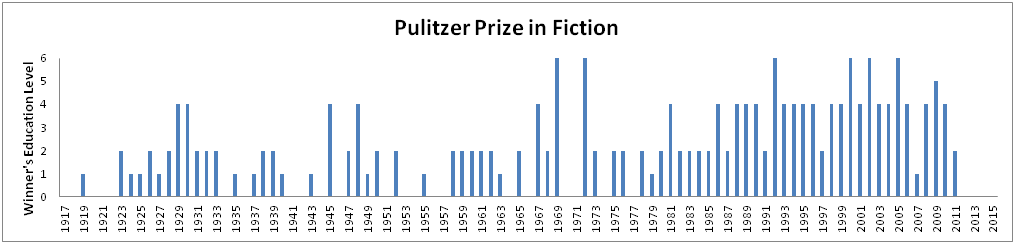

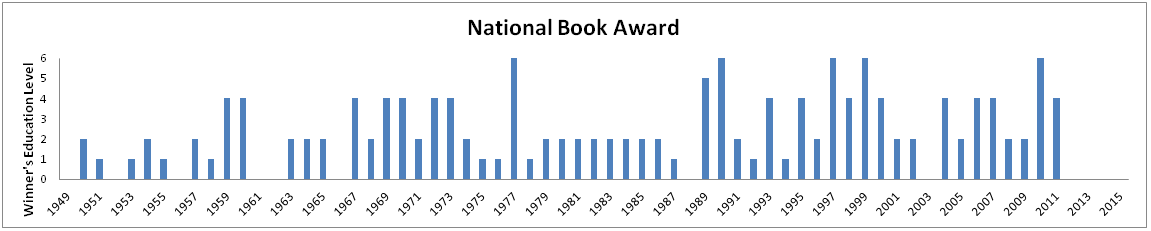

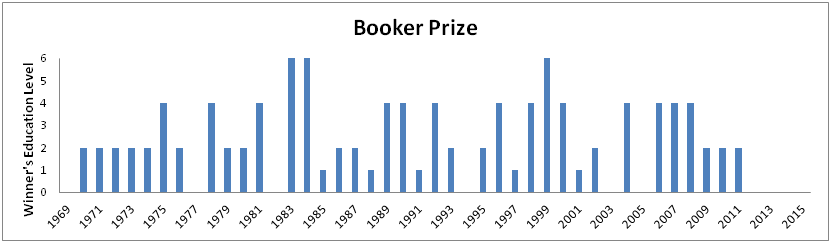

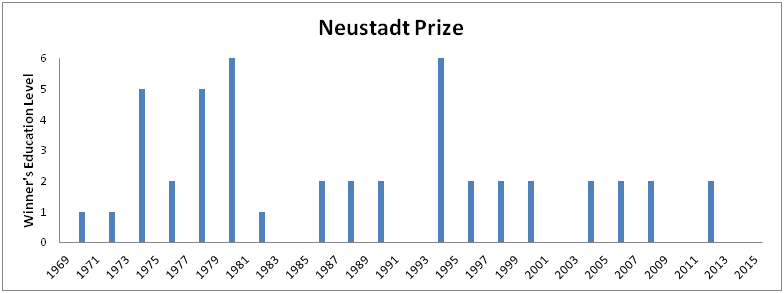

To present the data, I assigned a numerical value to each degree: BA = 2, MFA = 4, PhD = 6. No degree = 0 (i.e. highest level of education completed is high school or lower). I then assigned partial undergrad = 1 and JD = 5, which I felt best reflected their “status” relative to the major degree levels. I then made a bar graph of the numerical degree value by year.

And now, the results. All of the following comes with an enormous “small sample size” caveat.

First, consider the two awards with the longest history: the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, and the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Pulitzer is only American authors (including immigrants), while the Nobel is world-wide. Also, the Pulitzer is awarded for a specific piece, while the Nobel is awarded for the author’s entire body of work. This means the Pulitzer allows individuals to win multiple awards, which is not insignificant since we are trying to draw conclusions from only ~100 data points.

(click images for fullsize)

|

Nobel |

Pulitzer | |||

|

Degree |

Total |

Percent |

Total |

Percent |

|

none |

31 |

27.7% |

25 |

25.5% |

|

partial |

27 |

24.1% |

13 |

13.3% |

|

BA |

32 |

28.6% |

31 |

31.6% |

|

MFA |

4 |

3.6% |

22 |

22.4% |

|

JD |

11 |

9.8% |

1 |

1.0% |

|

PhD |

7 |

6.3% |

6 |

6.1% |

The Pulitzer Prize data shows a definite trend of higher degrees being more common in recent times. Six winners had advanced degrees from 1918-1969, then 23 had one between 1970-2012. There is a definite trend towards having a college degree in recent times, with the last degree-less winner being Jean Stafford in 1970 (after which no prize was given in ’71, ’74, ’77, or ’12).

The Nobel Prize, on the other hand, shows no particular trend in winners’ education levels. Having a degree is common throughout the history (Prizes were not awarded in some years), and having an advanced degree is rather common. If anything, there may be a slight trend away from the winner having an advanced degree in recent times, though it’s certainly not definitive.

It is basically impossible to draw any conclusions from this data. Taken together, it suggests that there could be a trend towards increasing significance in advanced degrees for American award-winning authors. World-wide, no such trend exists. This could be reflective of the relatively underdeveloped state of American higher education in the late-nineteenth century, when most early Pulitzer winners were born. However, it seems just as likely to me that recent authors who pursue higher education at all are more likely to pursue advanced degrees as well. Anecdotally, it seems like people with terminal Bachelor’s degrees in literature or creative writing tend to pursue (or at least, find) careers in journalism, show business, or teaching, as opposed to authoring novels. However, I have no data to support this.

Turning to additional literary prizes for additional insight is unfortunately unhelpful. There are two more awards given over similar timeframes with a similar dynamic to the Pulitzer/Nobel one discussed previously: the National Book Award (given to Americans) and the Man Booker Prize (given to citizens of the Commonwealth of Nations, as well as Ireland and Zimbabwe).

|

NBA |

Booker | |||

|

Degree |

Total |

Percent |

Total |

Percent |

|

none |

11 |

16.7% |

11 |

22.0% |

|

partial |

10 |

15.2% |

6 |

12.0% |

|

BA |

24 |

36.4% |

17 |

34.0% |

|

MFA |

15 |

22.7% |

13 |

26.0% |

|

JD |

1 |

1.5% |

0 |

0.0% |

|

PhD |

5 |

7.6% |

3 |

6.0% |

Most winners of the National Book Award (NBA) have college degrees (only 6 of 62 prizes went to someone without any college at all). There is little if any trend in advanced degrees amongst these winners. Notably, the first NBA winner with an advanced degree was Bernard Malamud in 1959 (he won again in ’67). He also won the Pulitzer in 1967, which could be taken as the first year of the modern trend of Pulitzer winners having advanced degrees.

There is no discernible trend in the education level of Man Booker Prize winners that I can see.

Finally, I would be remiss without mentioning the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. It is the youngest of the awards considered here (only one year younger than the Man Booker Prize), and like the Nobel Prize it can be awarded to citizens of any nation. However, unlike the others it is biennial, so far fewer Neustadt awards have been granted than the others. There is little trend in education level amongst the Neustadt winners; most of them have degrees, though if anything there seems to have been a trend away from advanced degrees among the winners in recent years.

|

Degree |

Total |

Percent |

|

none |

7 |

28.0% |

|

partial |

3 |

12.0% |

|

BA |

11 |

44.0% |

|

MFA |

0 |

0.0% |

|

JD |

2 |

8.0% |

|

PhD |

2 |

8.0% |

Finally, a comment on the percentages. Overall, 70%-80% of the winners have at least some college experience, and ~60% have a college degree. Only the Nobel Prize has more winners without a degree than with. The percentage of winners with a degree is slightly higher for the National Book Award and the Man Booker Prize, which could reflect the relative importance of higher education in the cultures of the US and the Commonwealth. Then again, between the small sample and the abundance of confounding factors, the difference could well be meaningless.

Overall, I take two conclusions from this exercise:

- Most “great” authors have a college degree, and few have no college experience at all.

- Many “great” authors, both in America and around the world, have advanced degrees of some sort, and this has been the case since at least the beginning of the twentieth century. The incidence of higher degrees among American literary prize winners may be increasing.

My original speculation was incorrect: higher education is significant to being a great author.

My reasoning for choosing engineering may still be correct, though. Approximately 40% of literary prize winners have zero or partial college educations, while I believe nearly every professional engineer has at least a Bachelor’s. Unfortunately, comparing the percentage of degree-less successful engineers to degree-less successful authors is far beyond my capabilities, if the data to do it even exists at all.

This isn’t to suggest that people entering universities with a passion for literature should not pursue a degree in that field. If anything, these results suggest that the modern trend towards highly-educated specialists has also permeated literature, and those intent on pursuing novel-writing should consider it likely that they will need college and likely post-graduate education to match the skills of the modern “greats.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.